History of the Camino de Santiago (& Legends!)

Have you ever wondered how exactly the Camino de Santiago began and how it's managed to continue well into today? I had the same question myself so set out to learn all about the history of the Camino de Santiago.

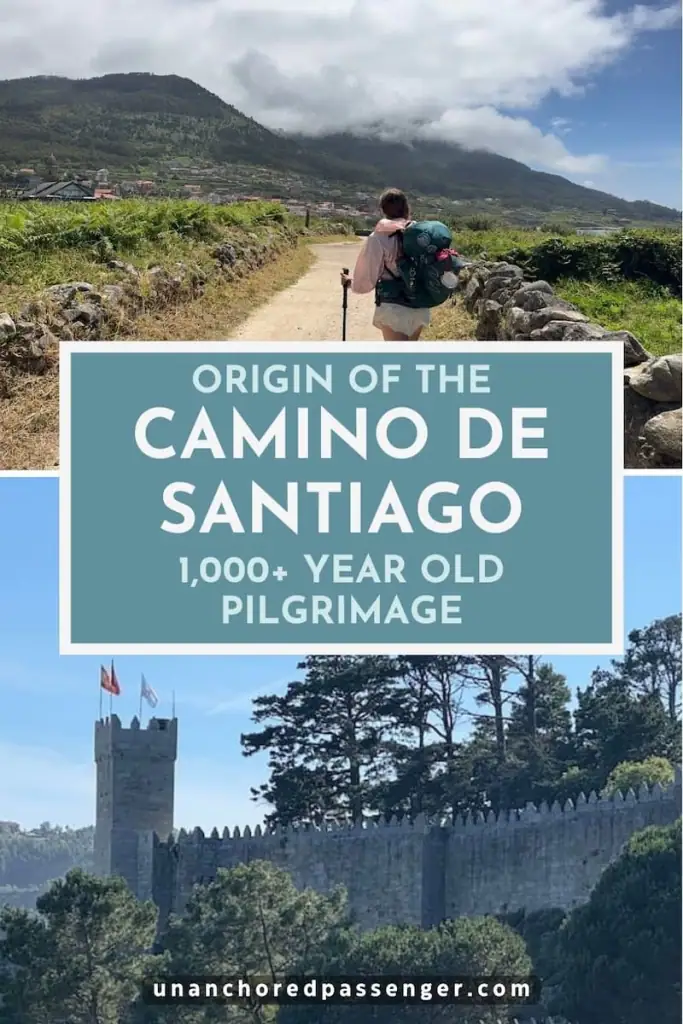

Pilgrims have completed the Camino de Santiago for well over 1,000 years now, walking from all over Europe to the alleged tomb of Saint James in Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It's one of the three most important Christian pilgrimages in the world, alongside those to Rome and Jerusalem.

I personally hiked the Camino Francés in 2023, spending 33 days walking almost 500 miles across Spain. I couldn't stay away so returned in 2025 to do the two main Portuguese routes.

Each time, I've found myself hearing many stories on the Camino's history (and legends) and wanted to learn more.

After my last Camino, I spent hours exploring the Museum of Pilgrimage and Santiago in Santiago de Compostela. I listened to over 8 hours of The Scholarly Pilgrim podcast from medieval historian John Seasholtz. I also spent some time digging into trusted sources like Brittanica and UNESCO.

So if you're planning your own Camino—or just fascinated by the centuries of myth, legend, and politics behind it—this post is for you. Keep reading to learn more about the history (and legends) that created the Camino we know today, including a fight with a dragon, issues with pirates, and the ongoing struggle between Christian and Muslim Spain.

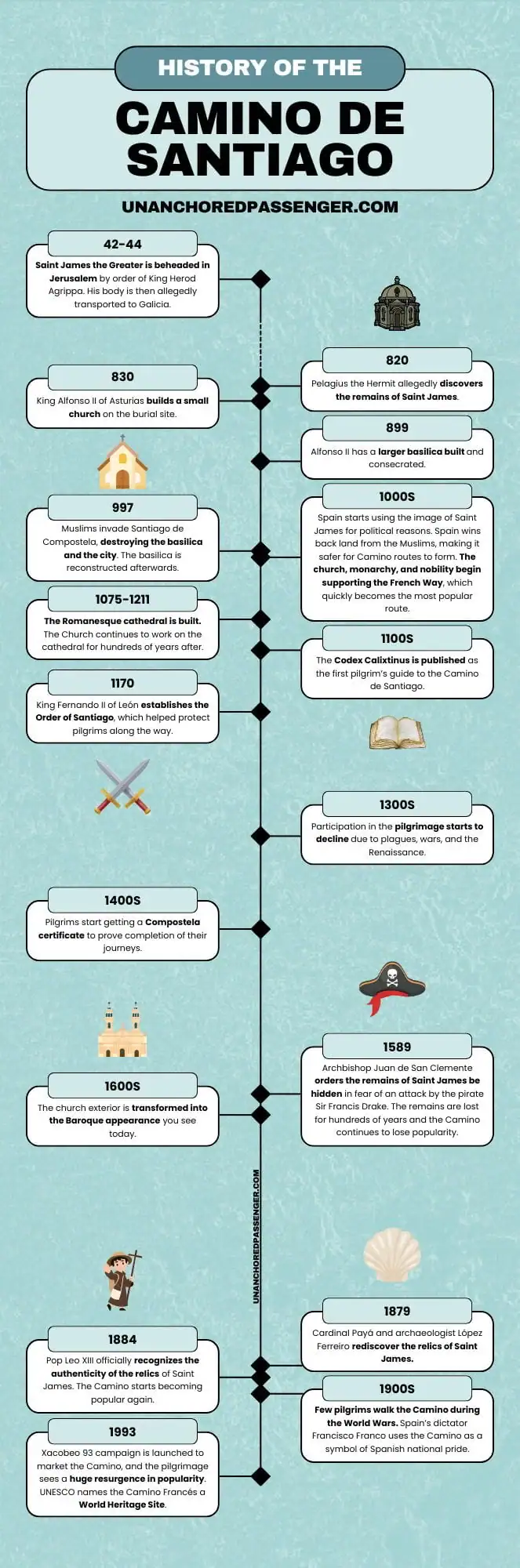

Timeline of Key Events

If you want a quick overview on the beginning of the Camino through modern times, check out this timeline. But if you're looking for more details, scroll on down to keep reading!

Origin of the Camino de Santiago

The Camino de Santiago traces its origins back to the alleged discovery of the remains of Saint James the Greater. But who was Saint James and how exactly were his remains discovered?

Who was Saint James?

According to the Bible, Saint James the Greater was son of Zebedee and Mary Salome and brother to Saint John the Evangelist, another Apostle. He was one of Jesus's closest disciples, accompanying him alongside Peter and John on some of the most important moments in Jesus's life.

While Eastern tradition claims Saint James preached in Judea and Samaria, Western tradition says he preached in Gallaecia (now Galicia, Spain) and what was then called Hispania (now modern day Roman Spain and Portugal).

Some writings dating from before the alleged finding of Saint James's remains mention his preaching in Hispania, but there's no credible historical evidence.

King Herod Agrippa ordered Saint James, known as Santiago in Spanish, beheaded in Jerusalem in 44 AD. He was the first of the Apostles to be martyred and the only Apostle whose martyrdom is recorded in the New Testament.

He had James, the brother of John, put to death with the sword.

Acts 12:2

Legend of the Translatio (Transport of Saint James's Body)

After Saint James was martyred, his disciples allegedly recovered his body and carried it by sea in a stone boat back to Galicia in what's called the translatio in Latin. They landed in Iria Flavia, not far from modern day Padrón on the Camino Portugués.

Pilgrims on the Portuguese Way today actually have the option to follow this same supposed boat journey. I did it myself in 2025 and found it such a cool way to experience this pilgrimage and all the history and legends behind it!

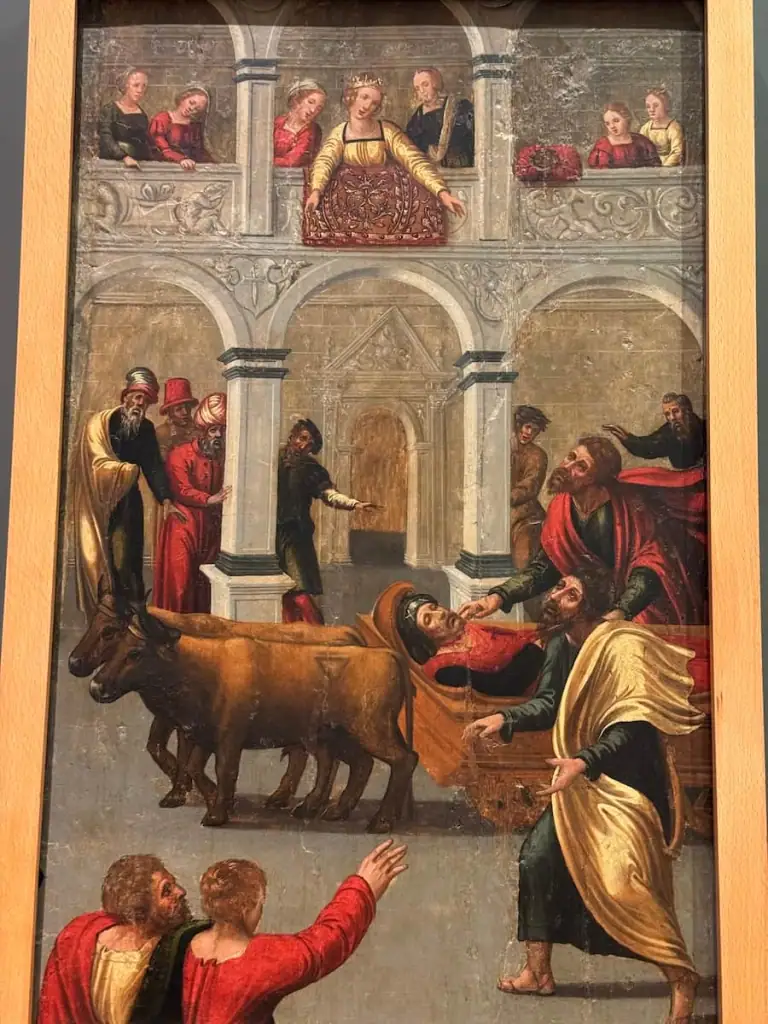

According to the pilgrimage museum, when the disciples arrived in Galicia, legend says they asked Queen Lupa for a place to bury Saint James. She sent them to the Roman Legate, where they were imprisoned until an angel freed them.

Lupa supposedly tried to trick them again, sending them to Mount Ilicino to find oxen to move the body. However, instead of oxen, the disciples found fighting bulls. Miraculously, the bulls were tamed, and the disciples also killed a dragon there.

Yep…you read that right, a dragon! Definitely one of the less believable parts of the story, but I love it. I think it really illustrates the sway the church had with the people at the time if they really had people believing a dragon fight took place.

After hearing how they overcame these obstacles, legend says that Lupa then converted to Christianity. Only then did she decide to offer them a place to bury Saint James.

Discovery of the Tomb and the First Camino

Starting in the 6th century, many believed that the Apostles were buried where they had been preaching. Various writings talked about this and some claimed Finis Terrae along the Galician coast as the burial site for Saint James.

In 820 a hermit named Pelagius allegedly discovered the remains of Saint James after he said he saw a bright star that guided him there. The local bishop declared them the lost relics of Saint James and his disciples.

According to the museum and The Scholarly Pilgrim, King Alfonso II of Asturias made the journey from Oviedo to Galicia to see the remains. Alfonso II confirmed the legitimacy of the remains and built a small church on the site around 830.

Alfonso II's journey to see the remains is considered the original Camino and what is now known as the Camino Primitivo, or Primitive Way.

I haven't yet walked the Camino Primitivo myself, but it's high on my list. I think it would be so cool to follow in the footsteps of the very first Camino. Plus, it's supposed to be a beautiful walk through some of Spain's most stunning mountains.

Are the Remains of Saint James Really Buried in Santiago de Compostela?

The burial site that Pelagius found was a mausoleum dating back to the 1st and 2nd century, according to the museum. Its design indicates it was made for an important person.

But was that important person really Saint James?

According to the Catholic church, yes. But according to everyone else? No one really knows.

The alleged finding of his remains certainly came at a convenient time for the Spanish as they were trying to win back the Iberian peninsula from the Muslims (more on that in a bit).

We don't even know for sure if Saint James had been preaching in Galicia, let alone if his remains are truly buried there. While some writings suggest he was preaching there, there's no solid evidence to prove it.

Some theories suggest the remains could actually be those of Priscillian, a heretic bishop who has been preaching in Spain and was executed in the 4th century.

In 1991, a forensic anthropologist studied some of the remains of Saint James the Lesser, which are also allegedly in the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela. He was only given access to those remains and wasn't able to examine those of Saint James the Greater.

His findings suggest that the skull attributed to Saint James the Lesser could potentially be that of Saint James the Greater due to the signs of decapitation on the skull. He notes, however, that the skull is incomplete as it's very fragmented and has significant structural damage from heat.

Plus, the church claims to have the full remains of Saint James the Greater in Santiago de Compostela. Yet at the same time, the church in the U.K. has claimed to have one of his hands for hundreds of years.

As you can see, there's a lot of conflicting evidence here. And even if experts had the chance to examine the alleged remains of Saint James the Greater, there's no way to truly verify if they're his.

If you ask me, I highly doubt they're really the remains of Saint James. But I don't think that really matters to the modern day pilgrim when it comes to the Camino.

Rise of the Cult of Saint James

After the alleged discovery of Saint James's remains, the Catholic church spread word of their findings and the story of the translatio. Many people at that time could not read, so these stories were spread via art and hymns.

The Scholarly Pilgrim shares that many medieval people believed close veneration of relics could cause that holy person to perform miracles or spiritual salvation on their behalf. By visiting important holy sites like Santiago de Compostela, pilgrims could also receive indulgences to forgive their sins.

The relics of martyrs were the most sacred of all objects for Christians. For this reason the discovery of the body of one of Jesus’s closest disciples and the first apostle to be martyred was an event of enormous consequence for the Christian communities of the 9th century.

Museum of Pilgrimage and Santiago

People, mostly from Galicia and the nearby Asturias, started making there way to Santiago de Compostela as early as the late 9th century. They were the first pilgrims on what is now known as the Camino de Santiago.

Significant numbers pilgrims didn't start visiting until the 11th century. By the 12th century, Santiago de Compostela had become one of the greatest pilgrimage destinations in the world.

Saint James as a Political Symbol

Saint James the Greater has been depicted in more ways than most Christian figures according to the pilgrimage museum. He's been shown as:

- An Apostle with a tunic and cloak, bare feet or sandals, and a holy book

- A pilgrim since he had been sent to preach in Hispania and had come to be identified with the Camino

- A knight fighting on horseback with the Spanish against the Muslims, Turkish Empire, and native people in the New World–ironically indigenous people later used a similar image in their fights against the Spanish

At the time of the alleged discovery of Saint James's remains, Christian Spain was quite small and Muslims dominated much of the Iberian Peninsula.

Having the supposed remains of Saint James gave the monarchy the ability to better unite Spain and fight against their enemies during that time and later on with future enemies.

They sure did find the supposed remains at a convenient time, didn't they?

This episode of The Scholarly Pilgrim podcast talks more about the image of Saint James as a knight, known as Santiago Matamoros, meaning Saint James the Moor Slayer:

Development of Santiago de Compostela

A small rural hamlet called Locus Sancti Iacobi emerged after the remains of Saint James were said to be found and the first church was built there around 830.

Not long after, Alfonso III of Asturias had a bigger basilica built, which was consecrated in 899. It was destroyed by Muslims in 997 along with the rest of the city and was rebuilt afterwards according to the museum.

Santiago grew into a prominent city from the year 1000. It continued to expand through the 13th century, especially with the growth of the church there.

People from all over Western Europe, referred to as Franks, began to move to Santiago de Compostela to take advantage of the growing commercial opportunities.

From the year 1000 Compostela grew into a city of great religious, political, economic and cultural importance. Its status as the last resting place of an apostle, the fact that it was one of the most important archdioceses in the Iberian Peninsula and the capital of a very large, well-populated feudal estate made it an attractive place to establish religious, political, educational and care institutions that all left their mark on the city.

Museum of Pilgrimage and Santiago

As the number of pilgrims visiting continued to grow, a bigger church had to be built to replace the previous one. The church started work on the Romanesque cathedral in 1075, which was later consecrated in 1211.

They continued to work on the cathedral for hundreds of years after. Most notably in the 17th century, the exterior of the cathedral was transformed into the Baroque style we see today.

Even if you're not religious, a visit to the cathedral is a must when in Santiago de Compostela. It's one of the most stunning cathedrals I've seen in Spain (and I've seen a TON of Spanish cathedrals).

It's so wild to think that the cathedral we see today first started being built almost 1,000 years ago.

Establishment of Camino de Santiago Routes

Pilgrims traveled from all over Europe to Santiago de Compostela, often starting directly from their homes and following along old Roman roads. While some traveled by sea, the majority traveled by land.

According to the pilgrimage museum, the main routes that emerged included the following:

- Camino Primitivo (Primitive Way) known as the original way connecting Asturias to Galicia

- Camino Francés (French Way) through northern Spain

- Camino del Norte (Northern Way) along Spain's northern coast

- Camino Inglés (English Way) from the northern Galician coastline to Santiago, often traveled by pilgrims who arrived on boat (however Vikings and pirates were a risk to those traveling by sea)

- Camino Portugués (Portuguese Way) from Portugal north to Santiago

- Finisterre-Muxía from Santiago to the western coast

- Vía de la Plata (Silver Way) connecting southern Spain to the north

These routes are all still popular among pilgrims today.

As the Spanish won back land from the Muslims, the monarchs and church at the time put their focus on building up the Camino Francés (French Way). In the 11th century, the Camino Francés became the most popular of all the routes and still is to this day.

When I hiked the Francés myself in 2023, I was in awe of all the history along the trail. I was able to see numerous historic churches and monasteries. While I enjoyed my walk along the Portuguese routes, there definitely wasn't quite as much history along the way like the Francés.

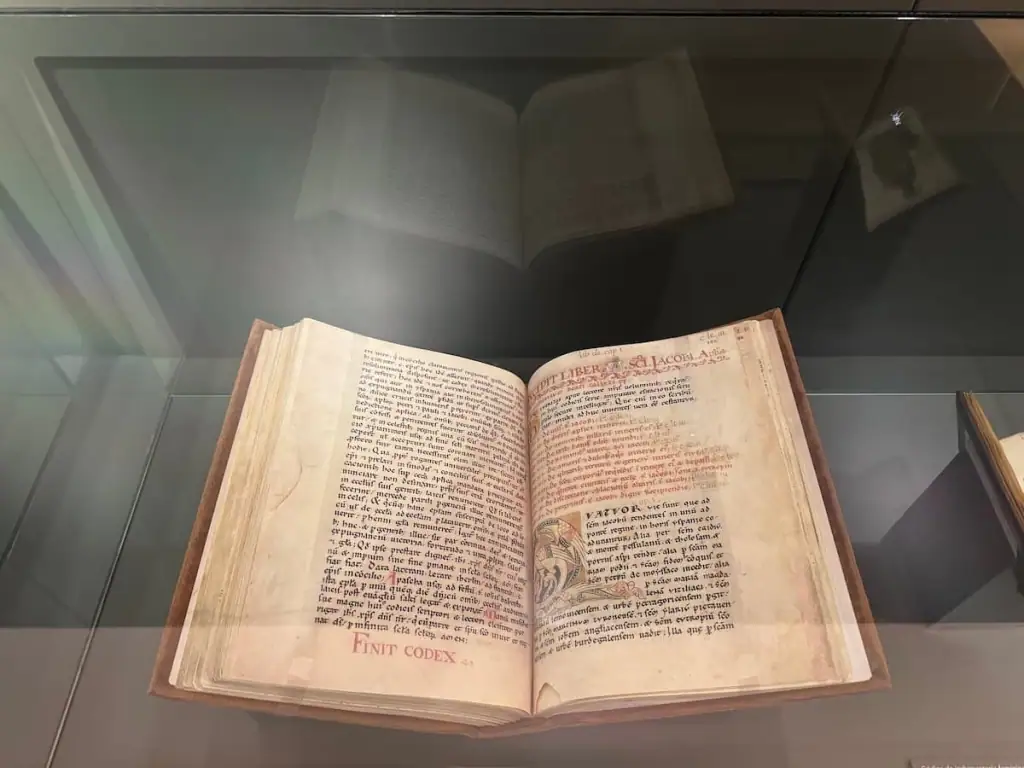

By the 12th century, pilgrims had their first official guidebook, the Codex Calixtinus. In addition to providing advice for pilgrims on the Camino, the book contained sections on:

- Sermons and homilies relating to Saint James

- An account of supposed miracles tied to Saint James

- The story of the translatio

- The legend of Saint James appearing to Emperor Charlemagne and encouraging him to fight the Muslims

Pilgrimage Infrastructure and Protection

The paths to Santiago de Compostela used to be very dangerous for pilgrims. Many even died along the way. In fact, the church even encouraged pilgrims to make wills before setting out on their journeys because this was such a common occurrence.

Pilgrims had to face dangers like river crossings, mountain passes, bandits, wolves, poisonous water, plague, and shady innkeepers. Plus, during the late 10th and early 11th centuries, pilgrims faced the added dangers of Viking and Muslim attacks.

I can't imagine walking the Camino during this time. Can you?

As the years went on, Christian Spain gained more land throughout the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims. This pushed the fighting southward, farther away from the Camino.

The church and monarchy also started to build up more infrastructure and protection for pilgrims traveling on the Camino, like hospitals, monasteries, and bridges.

More towns started to pop up along the way, incentivized by the monarchy to support the Camino. The towns offered pilgrims a place to stay, get food, and pray.

The Knights Templar started to monitor the Camino Francés beginning in 1142 according to The Scholarly Pilgrim. Not long after, around 1160-1170, King Ferdinand II founded the Order of Santiago. Both of these organizations helped guarantee security for pilgrims on the Camino.

Along the Camino Francés, you can even visit a Knights Templar castle that's still standing in Ponferrada. Visiting that castle was absolutely one of the highlights of my Camino.

With all this new infrastructure and protection in place, the 12th century soon became what's known as the golden age of the Camino because it had grown so much in popularity.

By the 14th century, pilgrims could receive Compostela certificates as official proof of their completed pilgrimage. Pilgrims still get certificates to this day.

Decline of the Camino de Santiago and Rediscovery

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela really started to decline between the 14th and 16th centuries. This happened for a few reasons according to the pilgrimage museum:

- Plagues, most notably the Black Death in Europe

- Wars in Spain

- The Renaissance and Protestant Reformation

To make matters worse for the Camino, the relics of Saint James were lost. In 1589 Archbishop Juan de San Clemente ordered the remains to be hidden because he feared an attack by the pirate Sir Francis Drake.

Yes, a pirate! It really was quite a time back then…

The remains were lost for almost 300 years until Cardinal Miguel Payá and canon and historian Antonio López Ferreiro rediscovered them in 1879. Pope Leo XIII officially recognized the authenticity of the relics in a papal bull Deus Omnipotens in 1884.

Modern pilgrimages started up again after this as did the revitalization of Santiago de Compostela.

20th Century to Present Day Revival of the Camino

As the Camino grew again, it faced some setbacks in the 20th century. Foreign tourism in Spain was reduced for quite some time during both World Wars (1914-1918, 1939-1945) and the terrible Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

After the Civil War, dictator Francisco Franco used the Camino as a symbol of national pride and supposedly as an attempt to unify Spain's many regional identities.

He restored an annual offering from the government to Saint James and reinstated the Apostle as the patron saint of Spain. His regime also forced Catholicism on the people of Spain, which increased interest in Catholic traditions like the Camino.

In spite of the terrible things Franco's regime was doing within Spain, its focus on foreign tourism led to a boom in visitors to Spain. His government spent large amounts of money marketing Spain for tourism, including the Camino.

While the Camino grew under Franco's regime, the number of pilgrims remained fairly low. It wasn't until after his death in 1975 that the Camino really started to grow.

Spain's turn to democracy and the establishment of Xacobeo 93 really led to a boost in the pilgrimage. Xacobeo 93 was a huge push by the Galician government to promote the pilgrimage during the Holy Year that year (when the Feast of Saint James, July 25, fell on a Sunday).

In 1993 UNESCO recognized the Camino Francés as a World Heritage Site and later added other routes in 2015. Since then, the Camino has continued to grow enormously each year.

Symbolism on the Camino

The Camino de Santiago has several symbols that have been around now for centuries. Most notable among them is the scallop shell.

According to a sermon in the Codex Calixtinus, the scallop shell was a symbol for good deeds due to its hand-like appearance. Pilgrims would purchase the shells upon arrival to the cathedral and would wear it on their clothes during their return journey home.

Pilgrims who wore the shell, according to The Scholarly Pilgrim podcast, were expected to adhere to God's commandments and forego their past sinful behavior, making a lifelong change that went beyond just the pilgrimage.

Pilgrims today often put the shell on their packs at the start of their journey. I did this on all three of my Caminos.

The pilgrim staff used by medieval pilgrims represented poverty and offered supposed protection from the devil. Pilgrims, no matter their class, were encouraged by the church to take a voluntary vow of poverty, imitating Christ, in order to fully atone for their sins and receive spiritual salvation.

You'll often see the Cross of Saint James in relation to the Camino as well. It's a red cross meant to look like a sword with a long base and fleur-de-lis type designs on the three ends on top.

This cross was the emblem of the Order of Santiago and symbolizes the defense of the Christian faith. Today you might see it painted on some scallop shells and also on top of tarta de santiago, the almond cake common throughout Galicia.

Camino de Santiago Pilgrims Through the Ages

While it's certainly interesting to learn about the start of the Camino and the way Spain's political and religious forces shaped it, I personally find it even more interesting to think about the pilgrim experience hundreds of years ago.

The Camino is certainly a challenge for modern day pilgrims, but what was it like for pilgrims so long ago? I really can't imagine walking so far in the clothing and shoes they had back then, not to mention all the other challenges they faced.

The First Camino Pilgrims

The first pilgrims started making their way to Santiago de Compostela sometime by 886, not long after the supposed finding of the Apostle's remains. Most early pilgrims remain anonymous, but there are records of some more prominent pilgrims.

The first known foreign pilgrim was a French man named Bretenaldo who walked around the year 920. Bishop Godescalco of Le-Puy, France was another early recorded pilgrim and walked in 950.

Early pilgrims included kings, nobles, clergy, and commoners. Some pilgrims were even forced to walk as penance.

Why did these people walk the Camino? Particularly during some of its more dangerous years when there was little infrastructure, a war with the Muslims not far from the path, and little protection for pilgrims?

It [the pilgrimage] is interpreted as a way of perfection and is walked out of pious devotion (orationis causa) or to ask for the grace of God. For some people it is a “way of atonement” in order to fulfill a promise. For others it is a “way of purification,” a way of doing penance as happens in the years of “Gran Perdonanza” (Great Forgiveness) in order to earn the established indulgences.

Museum of Pilgrimage and Santiago

According to the The Scholarly Pilgrim podcast, people in that time were highly concerned about spiritual salvation after death. They also believed miracles were somewhat of a regular occurrence.

The Camino provided the perfect opportunity for people at that time to seek out both spiritual salvation and miraculous interventions.

Pilgrims would often travel in groups and with merchants to try and stay safe from dangers like wild animals, bandits, and criminals. Most pilgrims traveled on foot, but those of privilege used animals or carriages.

Their clothes usually included a cape, a cloak, a broad rimmed hat, and leather shoes. Most carried a staff, basket, and sporran as well as a gourd to carry water or wine. Their outfits were fairly standardized so they could be easily identified as pilgrims.

Unlike today, if pilgrims back then were even lucky enough to get a bed on the way, it was usually made of straw and they had to share with others. Meals typically included just bread and wine. Occasionally they'd get a little meat or fish.

Medieval Women on the Camino

Unlike today's Camino that sees more women on the trail than men, women did not make up many of the pilgrims in the Middle Ages.

During that time, women traveling alone were often associated with adultery, sex out of wedlock, and prostitution. Female pilgrims were seen as dangerous because they could tempt men into sinful behavior and jeopardize their chance of spiritual salvation.

Aside from this, women were also expected to remain at home to take care of the household.

Medieval women faced many prejudices related to an overwhelming belief, supported by the church, that they were inferior to men. Women were expected to either live chaste lives in religious institutions or obediently support their husbands, have children, and otherwise remain invisible within their homes. Some brave and devout women from all classes of society overcame these barriers and made the long and dangerous pilgrimage to Compostela.

John Seasholtz, The Scholarly Pilgrim Podcast

In the Middle Ages women were required to get permission from their husbands to go on the Camino. As you can imagine, this rarely happened.

This didn't keep women from making the pilgrimage. However, those who did were likely mostly women who went with their husbands or traveled after they had died.

Many women went on pilgrimage for similar reasons as men–in search of spiritual salvation and assistance from the saints. Some women also traveled on the Camino to ask for help with fertility or medical cures.

Travel during the Middle Ages was quite dangerous at times, even for men. So like men, many women traveled in groups. Even so, they often feared assault from men during long isolated stretches on the Camino or while spending the night in cramped quarters.

I truly can't imagine what it would've been like to walk as a woman back then. It certainly must have taken a lot of courage, and I am in such awe of these medieval women who walked the Camino!

The Scholarly Pilgrim podcast has a great episode dedicated to medieval women on the Camino that I used to learn about this topic. You can check it out here if you want to learn more:

Notable Pilgrims Over the Years

While many pilgrims have remained anonymous over the years, there have been notable pilgrims throughout history. Some of those pilgrims include the following individuals:

- Queen Isabel of Portugal walked the Camino twice in 1325 and 1335.

- The Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragón and Isabella I of Castile made the pilgrimage in 1486.

- Former U.S. President John Adams journeyed along the Camino backwards to Paris in 1779-1780 after being appointed by Congress to negotiate peace treaties there with Great Britain.

- Pope John Paul II walked the Camino twice in 1982 and 1989.

- Paulo Coelho, beloved author of The Alchemist, walked the Camino in 1986 and wrote a book about it.

- Stephen Hawking, theoretical physicist and cosmologist, symbolically did a small section of the Camino in 2008.

- Martin Sheen, star of the movie The Way walked some sections of the Camino Francés while filming in 2009.

- Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy walked a small section of the Camino together in 2014.

- Members of the K-pop group g.o.d. walked the Camino together, which was filmed as part of a show that released in 2018. This is one reason why the Camino has grown in popularity among South Koreans.

- José Andrés, renowned chef and humanitarian originally from Spain, has walked the Camino in recent years.

- Various members of the Spanish royal family have walked the Camino over the years. Same with the Belgian royal family.

The Camino Today

Today, the Camino continues to grow in popularity each year. Last year, almost half a million pilgrims completed the journey.

Not only are more people finding out about the Camino each year, but the journey is certainly much easier for modern day pilgrims with today's comforts and technology.

In addition, all kinds of people walk the Camino de Santiago today. While the Camino started out as a religious pilgrimage, those who journey its path today do so for all kinds of reasons.

On my Caminos, I've met pilgrims from all over the world and of all ages. While I'm a Christian and enjoyed the spiritual aspect of the Camino, I'm not Catholic and my main reason for hiking was to go on an adventure and heal after a terrible breakup.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some answers to frequently asked questions when it comes to the history of this ancient pilgrimage route.

Why is the Camino de Santiago sacred?

The Camino de Santiago is sacred because people have been journeying along it for over a thousand years now in search of spiritual salvation. Pilgrims aim to make it to Santiago de Compostela, Spain where Saint James the Greater is allegedly buried.

What does the word “camino” mean?

The word “camino” is Spanish for “walk” or “way.” It comes from the Latin word “caminus,” which is said to have come from the Celtic word “camminus.” In English, “Camino de Santiago” directly translates to the “Way of Saint James.”

Why do Catholics walk the Camino?

The Camino de Santiago originated as a Catholic pilgrimage for people to seek spiritual salvation and the assistance of Saint James by visiting his relics (his remains). While not everyone walks the Camino today for religious reasons, some people still do.

What do you call people who walk the Camino?

People who walk the Camino are typically referred to as “pilgrims,” or “peregrinos” in Spanish, since they're on a pilgrimage.

Learn More About the History of the Camino de Santiago

There is so much to know when it comes to history of the Camino de Santiago. This article really just scratched the surface. If you want to dig deeper, I highly recommend:

- Visiting the Museum of Pilgrimage and Santiago in Santiago de Compostela (one of the top things for pilgrims to do in the city!)

- Listening to The Scholarly Pilgrim podcast by John Seasholtz

- Purchasing a guidebook for your Camino that can walk you through more history specific to your route

I personally LOVED reading my guidebook and learning, for instance, about bridges where pilgrims used to be targeted by bandits. It really made me appreciate my journey even more.

Next Step: Read About Why Pilgrims Today Walk the Camino

Now that you've learned more about the history of the Camino, fast forward to today and read this article next to get insights into why modern pilgrims walk the Camino.